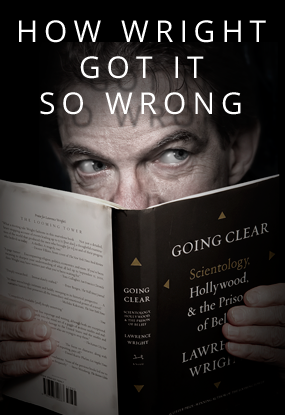

A Correction of the Falsehoods in Lawrence Wright's Book on Scientology

Both [Michael] Pattinson and his attorney say they were driven into bankruptcy.

>> True Information: Who is “his attorney”? The unnamed attorney in this passage is Graham E. Berry. Allegations from documents prepared by Mr. Berry, that were thoroughly discredited long ago, appear throughout the book—although they are never sourced to Mr. Berry by name. We suspect this is because Mr. Wright was aware of evidence tied to Mr. Berry that cannot pass the “laugh test.” Yet, Mr. Wright’s dependence on Mr. Berry, Mr. Berry’s paid witnesses and stories that Mr. Berry circulated and that later unraveled under scrutiny, fatally infect Going Clear. In addition to representing Michael Pattinson (page 309) and Garry Scarff (pages 281, 400 and 408), Mr. Berry’s clients who are cited in Going Clear include: Vicki Aznaran (pages 178, 179, 184, 219, and 345); Andre Tabayoyon (pages 180, 203, 207-208, 270 and 345); Hana Whitfield (pages 16 and 374); and, Robert Vaughn Young (pages 138, 183, 184, 196, 392 and 396).

In his interview with the Daily Beast, Mr. Wright defended his use of Garry Scarff saying he had interviewed Scarff with his attorney—again referring to Graham Berry.

Who is Mr. Berry?

Mr. Berry is a vehement anti-Scientologist whose own actions have decimated his reputation and credibility. Mr. Berry’s penchant for unethical behavior and self-destruction can be summarized as follows:

- he was assessed more than $100,000 in sanctions for harassing and frivolous litigation tactics, some unrelated to Scientology;

- he was dismissed by his law firm after paying a fact witness to prepare a perjured declaration;

- he declared bankruptcy after trying to run his own law practice;

- he was declared a vexatious litigant by the Los Angeles Superior Court (and consequently forbidden from ever filing another lawsuit without court approval); and,

- he was suspended from the practice of law by the California Bar for harassive litigation tactics and misusing client funds.

In reporting on his May 2002 suspension by the California Bar, the Los Angeles Daily Journal noted:

“In 1998, [Berry] began treatment for depression and began attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and has remained sober since that time. As a result of his medical condition, he closed his law practice in late 1999 and filed Chapter 7 bankruptcy.”

Mr. Berry’s journey as an anti-Scientologist began in 1994, when he was an associate in a Los Angeles law firm. One of his clients included a psychiatrist with a $1 million insurance policy who was a defendant in Church of Scientology International v. Steven Fishman and Uwe Geertz. According to court records, Mr. Berry squandered the money by hiring former Scientologists to manufacture false statements to use in the case. For example, Mr. Berry paid $17,000 to Andre Tabayoyon for a false declaration concerning conditions at Golden Era Productions, the Church of Scientology’s international film production facility. This false declaration is the source of some bizarre tales cited in Mr. Wright’s book, including that “explosives were placed around the perimeter” (of Golden Era Productions (page 203)) and that a field of wildflowers were planted for visiting celebrities (page 203).

By January 18, 1995, the senior partners of Mr. Berry’s firm had been apprised of the lack of credibility of the Tabayoyon affidavit and withdrew their support for it, stating in writing:

“The Church of Scientology International filed a number of declarations which make certain assertions regarding the veracity of Mr. Tabayoyon, which I enclose for your review. Please note this firm will no longer be utilizing the declaration of Mr. Tabayoyon nor will we assist in its publication or dissemination by others.”

Mr. Berry was then dismissed from his law firm.

Mr. Berry also purchased a so-called expert witness statement from Vicki Aznaran. She provided an eight-page signed declaration, but Mr. Berry filed a 19-page declaration to which he had added allegations Ms. Aznaran neither wrote nor agreed with. He did the same with her husband’s declaration. Ms. Aznaran testified in a declaration of May 19, 1994:

“I gave no authorization for my declaration to be changed after I sent the signed copy of it to Mr. Berry and the changes made to my declaration were made without my knowledge or consent. Mr. Berry never contacted me after he filed the manufactured 19-page version of my declaration. Had I not later obtained a copy of the declaration filed by Mr. Berry from another source, I never would have found out about any of these alterations.”

Other statements Mr. Berry bought were from anti-Scientologists Robert Vaughn Young and his wife Stacy Brooks. Although not attorneys themselves, the Youngs were paid attorney-level wages by Berry to draft or edit many of these statements, including the declarations of Andre Tabayoyon, Hana Whitfield, Vicki Aznaran and their own. They were all riddled with false claims, innuendo and speculation masquerading as testimony. Ms. Brooks later recanted under oath by making the following statement about what she and her husband had done for Mr. Berry and others:

“From 1993 through 1998, I made my living consulting with attorneys and writing affidavits and declarations in support of litigation that those lawyers were pursuing against various Scientology entities…those attorneys were Graham Berry ….

“It had been my understanding that I was free to use language that was extremely biased against Scientology in order to prejudice the courts as much as possible….

“The Fishman case was the first case I worked on, and it… was also in the declarations for this case that I made the most embellished and unsubstantiated statements about Scientology.”

As part of his representation of Fishman and Geertz, Mr. Berry procured a false deposition from Garry Scarff that Mr. Scarff later recanted under oath:

“12. During the course of the deposition, my false testimony included the following assertions. I knew that the statements I made would be used against the Church, and that though they would surely deny them (as the events never happened), they would be recounted anyway, and it would create negative publicity and sentiment against the Church.

“a. I made up a story that I had conspired with attorneys Kendrick Moxon, Timothy Bowles and Laurie Bartilson, as well as with investigator Eugene Ingram, to murder CAN’s Executive Director, Cynthia Kisser, and San Francisco attorney, Ford Greene, who had represented individuals in legal actions with the Church. The truth of the matter is that no such meeting was ever held and I was never ordered or asked to murder anyone and I completely fabricated the story with the knowing participation of Mr. Berry. I never even met Mr. Moxon until he appeared for a few minutes during one of the sessions of my deposition. I luckily recognized him then only because I had seen his photograph in a media article, so I feigned having met him before to try to bolster my credibility.

“b. That I had been a member of the Church of Scientology, and an “operative” conducting illegal or unethical activities on behalf of the Church, since the early 1980’s. In fact, I have never even been a member of the Church, much less an employee or “operative” for any Church of Scientology. I forged invoices and similar documents to support my false claim of having taken various Church religious services. Nor have I ever done anything illegal or unethical at the instruction of, on behalf of, or with the knowledge of any member of the Church of Scientology. To the contrary, I was specifically directed by representatives of the Church that I was not to do anything illegal or unethical while educating the public about CAN and told that, should I do so, they would immediately cease all contact with me.”

Many of the declarations procured by Mr. Berry for the Fishman action were dumped into the record purportedly in support of an application for legal costs. They were all stricken from the record as having been improperly filed, with the Court commenting at the hearing: “They aren’t going into evidence in this case. I didn’t—I wasn’t very successful in turning off the junk—so it continued to file in.”

One of Mr. Berry’s harassing lawsuits against the Church of Scientology was a malicious prosecution case filed in State Court in Los Angeles. In that case the court re-examined all of the declarations that Mr. Berry had tried to file in the CSI v. Fishman/Geertz case and then some, ultimately finding against Mr. Berry’s clients and dismissing the case on summary judgment in June 1996.

Mr. Berry represented Michael Pattinson, whose lawsuit was dismissed five times. After Mr. Berry repeatedly failed to comply with the court’s orders, the presiding federal court judge found his conduct harassing and awarded the defendant attorney’s fees. The judge subsequently ordered sanctions in the amount of $28,484.72 against Mr. Berry.

After failing with the Pattinson case, Mr. Berry then pursued without success his own frivolous litigation against Scientology churches and individuals. In these actions, Courts repeatedly assessed sanctions and attorneys fees against Mr. Berry, so that by the time he declared bankruptcy in 1999, they totaled more than $100,000.

In California, a person who files at least three suits based upon false or unsupportable information for the purpose of harassment may be declared a “vexatious litigant.” Such a finding forbids the offender from filing any future suits without prior approval from the court. Three different judges ruled Mr. Berry brought unsupportable claims to harass Scientology churches and their leaders. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Alexander Williams then stated to Mr. Berry:

“With all the due respect, Sir, I have to sadly state that if there is such a thing on God’s green Earth as a vexatious litigant, you, Sir, sadly, are it.”

The Court declared Mr. Berry to be a vexatious litigant on August 20, 1999.

In May of 2002, Mr. Berry was suspended from the practice of law by the California Bar for his continued pattern of misconduct, including the filing of harassing and frivolous litigation and the misuse of client funds. In an attempt to escape responsibility for his offences, Mr. Berry unsuccessfully used his substance abuse problems and mental health issues as excuses for his conduct.

Mr. Berry’s failed cases and their discredited supporting “evidence” are key source material for Mr. Wright. Mr. Wright prohibits his readers from thoroughly evaluating the public record. As a result, they are denied the chance to decide for themselves the honesty of the Berry witnesses cited in Going Clear and the credibility of their bizarre tales that Mr. Wright accepted at face value.

As with much of his book, Mr. Wright failed to properly vet for the reader his sources and the information he was providing. The courts agreed Mr. Berry and his cases lacked credibility to the point that they felt compelled to discipline him. Mr. Wright owed it to readers to write the full story, not conveniently leave out critical details that painted a biased, distorted picture of the Church.

The Investigation